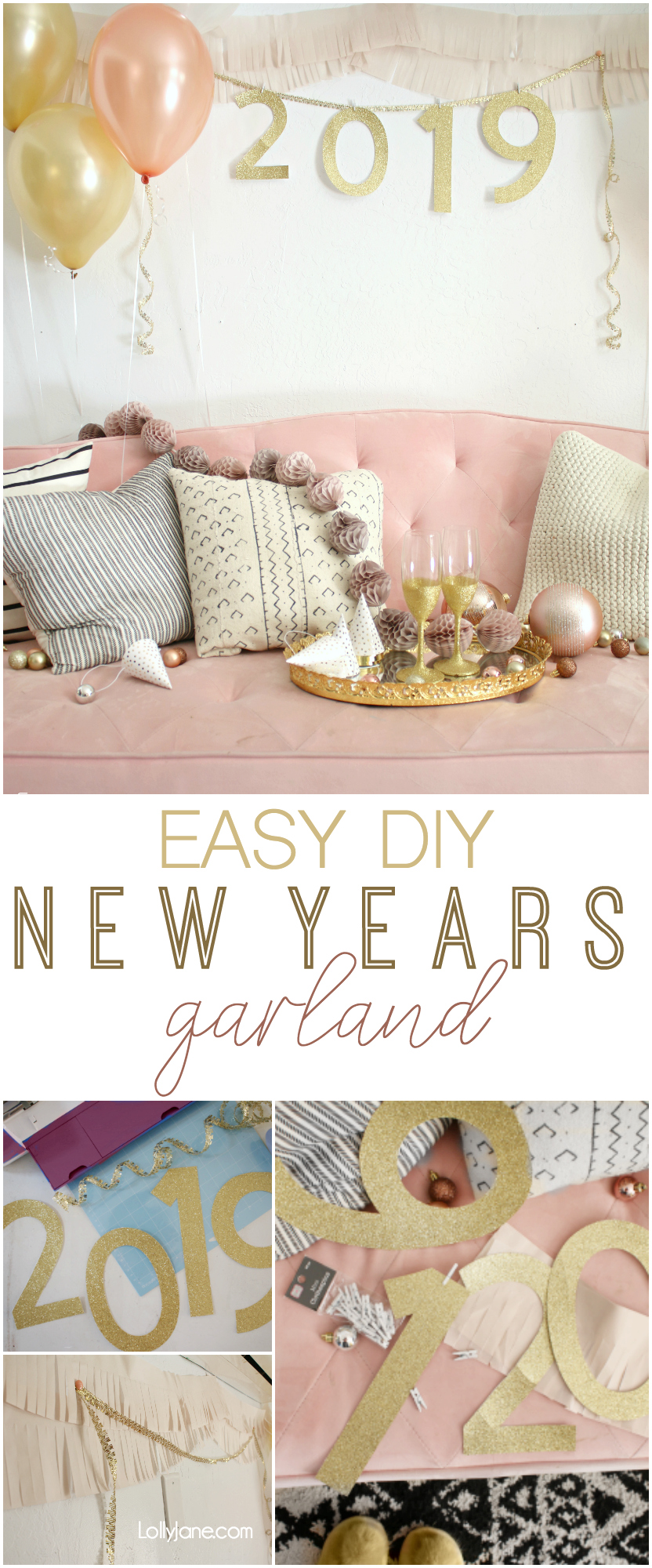

DIY New Years Eve party garland

Ring in the new year in style! make your own eASY new years eve party garland in just a few minutes and pair with a few party supplies to create a festive party backdrop in no time!

Today’s post is sponsored by JOANN. As always, opinions are our very own but we really do love JOANN!

New Years Eve Party Garland

Bring on the New Year! I love having older kids that can hang until the clock strikes midnight so this year, instead of leaving them with a sitter, we’re planning a family style New Year Eve party. I wanted a spot that the tweens/teens could use a selfie station but that could also double as a sitting area for adults so I headed to our local JOANN and got to work collecting this and that to create the perfect space. Once I got home, I whipped up an easy New Years Eve party garland in a matter of minutes!

Easy New Years Eve Party Backdrop

I found a handful of pretties in the most gorgeous golds to do just that! Keeping it simple, I started with 2 layers of a rose gold pink fringe paper from the party section at JOANN. There was enough to layer fringe all the way down to create a backdrop solo but I didn’t want it to be TOO busy so I settled on a few rows instead to create a banner.

Supplies to Make a New Years Eve Party Garland

- Glitter Cardstock, 12×12 x2

- Gold Fringe Ribbon

- Mini White Clothespins

- Cricut Die Cutting Machine, (OR pencil + scissors)

- Tacks

How to Make a New Years Eve Party Garland

- Create/Cut the numbers 2, 0, 1, 9 with your cutting machine (I have a Cricut Explore Air 2) but you can also cut these by hand, (draw block numbers on your gold card stock and cut out.) I sized mine just under 6″x”6.

- Tack up a strip of gold fringe ribbon the length of your backdrop.

- Hang each letter from mini clothespins, (I found mine in the paper aisle at JOANN) clipped directly onto the gold fringe ribbon.

Voila! Quick and easy New Years Eve bunting FTW!

I accented the rest of the space with beautiful XL ornaments in gold and rose gold hues and scattered matching mini ornaments across my pink couch. I love this garland that looks like little disco balls in the prettiest lavender gray hue that breaks up all of the golds going on and pulls my own decor in. Bet you thought those gorgeous glass champagne flutes (sparkling cider for us!) were a DIY but nope, JOANN made it extra easy and sells them as-is. Yesss!

I simply layered them on top of my grandmothers vintage gold tray and they are the perfect touch to polishing off this look.

I left a pile of the cutest gold and polka dot party hats, also from the party section at JOANN, on the tray for guests to use when the countdown starts. And, it happened to fit my Goldendoodle, Newman, perfectly! 😉

Pulling together a backdrop for New Years Eve, or any celebration, doesn’t have to be overwhelming. Head to your JOANN and be sure to browse ALL of the sections to simply grab what works for your own space!

- Save the Date Gold Toasting Flutes

- Cheer & Co. Mini White Clothespins

- Cheer & Co. Fringe Backdrop Kit (pearlized blush)

- Cheer & Co. Backdrop Kit Pom Poms (pearlized gray)

- Cheer & Co. Mini Party Hats

- Cricut Glitter Cardstock

- Maker’s Holiday Christmas 3pk Boxed Ornaments

- Maker’s Holiday Christmas 42pk Mini Boxed Ornaments

- Cascade Holiday Gold Fringe Ribbon

- Cricut Explore Air 2 (mint)

- Cricut Explore Air 2 (colbalt blue)

- 70+ Styles of 2019 FREE Printable Calendars

- 23 Easy NYE DIY Ideas

- 20+ Free NYE Printables

- Easy DIY Fur Numbers

- NYE Party Box Gift Idea

- Circular NYE Wall Decor

DIY New Years Eve Party Garland

Materials

- Glitter Cardstock, 12×12 x2

- Gold Fringe Ribbon

- Mini White Clothespins

- Cricut Die Cutting Machine OR pencil + scissors

- Tacks

Instructions

- Create/Cut the numbers 2, 0, 1, 9 with your cutting machine (I have a Cricut Explore Air 2) but you can also cut these by hand, (draw block numbers on your gold card stock and cut out.) I sized mine just under 6″x”6.

- Tack up a strip of gold fringe ribbon the length of your backdrop.

- Hang each letter from mini clothespins, (I found mine in the paper aisle at JOANN) clipped directly onto the gold fringe ribbon.

- Voila! Quick and easy New Years Eve bunting FTW!

Notes

Oh thank you, Kerri! Sweetest comment!! XOXO

You girls are seriously AHHHMAZING! I mean I never in a million years would think that a pink couch could look soo dang cute! And that pup is probably the cutest dog I’ve EVER seen! I hope you ladies have a fabulous New Year! I can’t not wait to see what you have in store for 2019! 🙂